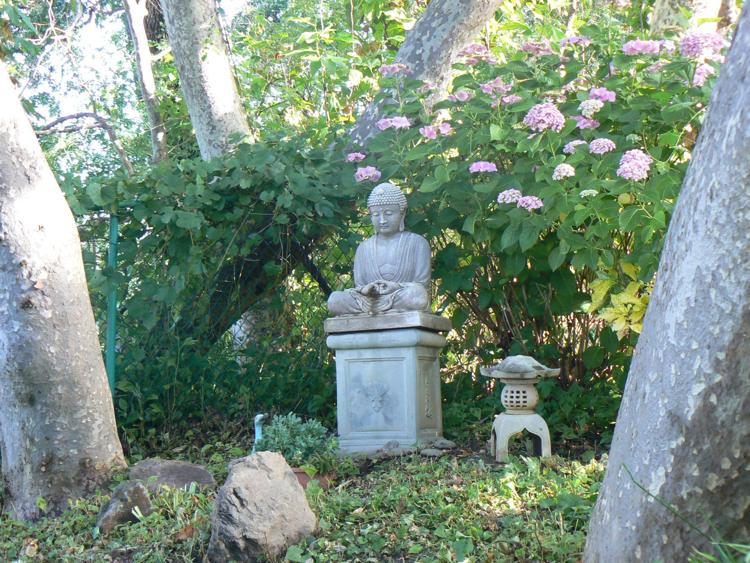

Faith and Values: To aid the environment, Buddhism teaches us to see interdependence between nature and living

Source: spokesman.com This week’s column comes from Spokane Faith and Values’ Ask a Buddhist series. “Does Buddhism contain any practices […]